Collaborative presentation with Pamela Weissenberg, Mexico City Condo London 2024

All perception—indeed, all our experience of the world is embodied. We cannot understand the world we live in, nor can we interact with each other or act on the environment around us, without our bodies. Everything we know, everything we do, and everything we are, is mediated by the body. i

More questions than answers (such is life): Can we ever gain an understanding of our own body? No, would seem to be the obvious response… If every experience shapes us, we are therefore in a constant state of intangible flux, a condition of endless becoming. Wherein – the deck stacked against us from the outset – even the simplest image of ourselves, our reflection, we see in reverse. Thanks to rudimentary physicsii, this fundamental discrepancy between our self-image and how others see us, the rift between our imagined self and desired self, suggests the yearning for our bodies to exist beyond their (actual – what-so-ever-that-is) physicality. But even a willed projection of mental image is sketchy, given that ‘actual’ representation is undermined by the decreasing faith in veritas in our fabulous post-truth society. (The argument of “it’s my truth” is contemporaneously given relative legal weight). We can of course digitally alter and heavily edit images of ourselves to select which self is presented as the preferred ‘real’ to the virtual eyes watching us (imagined/desired/paranoid?), as we can laboriously construct avatar selves that live solely, or dialectically, in a parallel digital world.

If the above is a willing fiction, then perhaps the closest we get to unwilling fact is the prevalence of video surveillance, so active that images collected in public spacesiii can construct a detailed and accurate ‘portrait’ of self (us). A concealed camera scanning our retina can reveal our current appearance and project a version of ourselves decades into the future. Which are we: our faulty perception of our real, or ‘their’ real? Does all of this indicate that we are losing any/all control over our identity? Or, with the tools and skills to manipulate versions of ourselves being more accessible than ever, are we more in control of our images? Are we, in reality, enhanced?

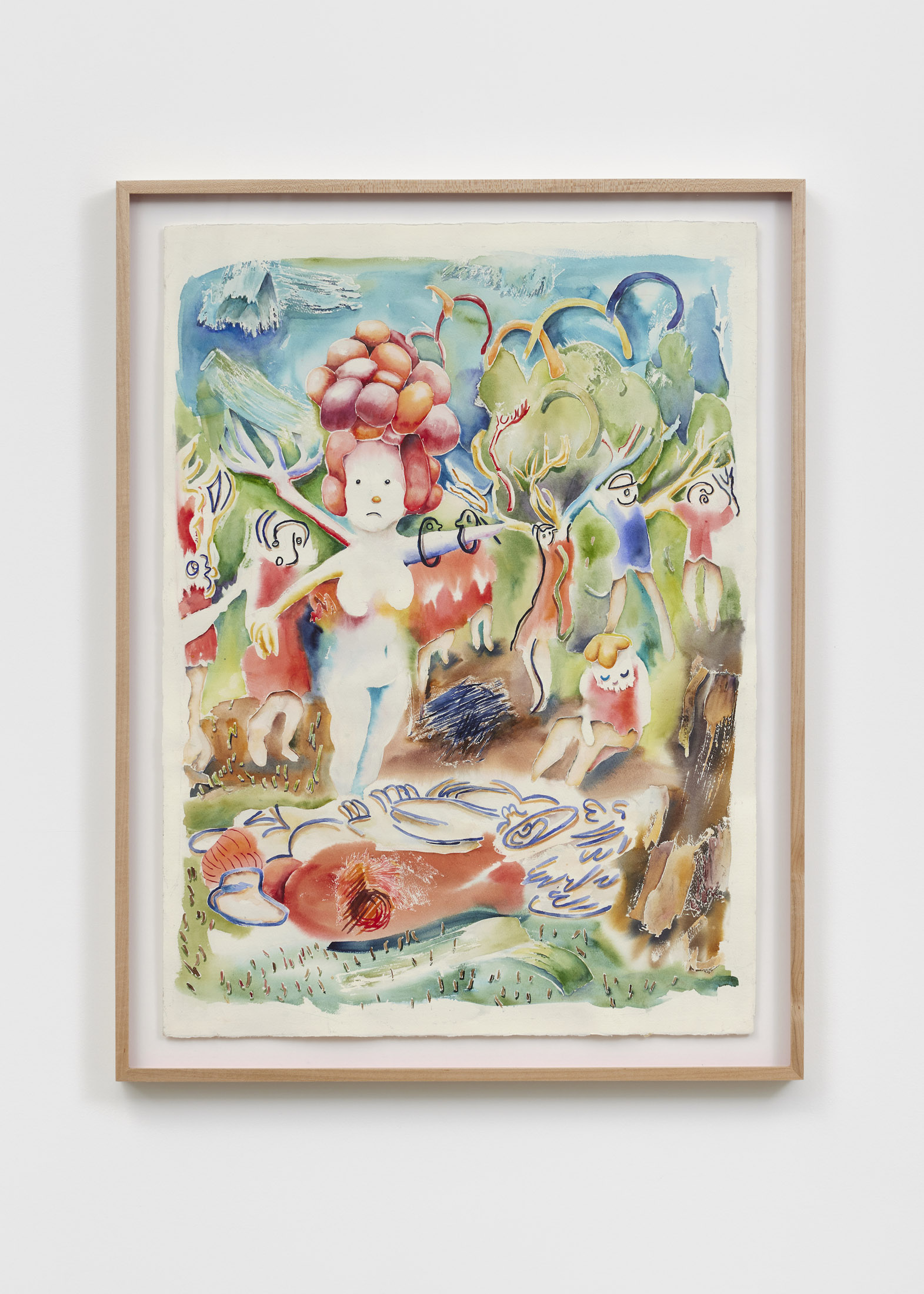

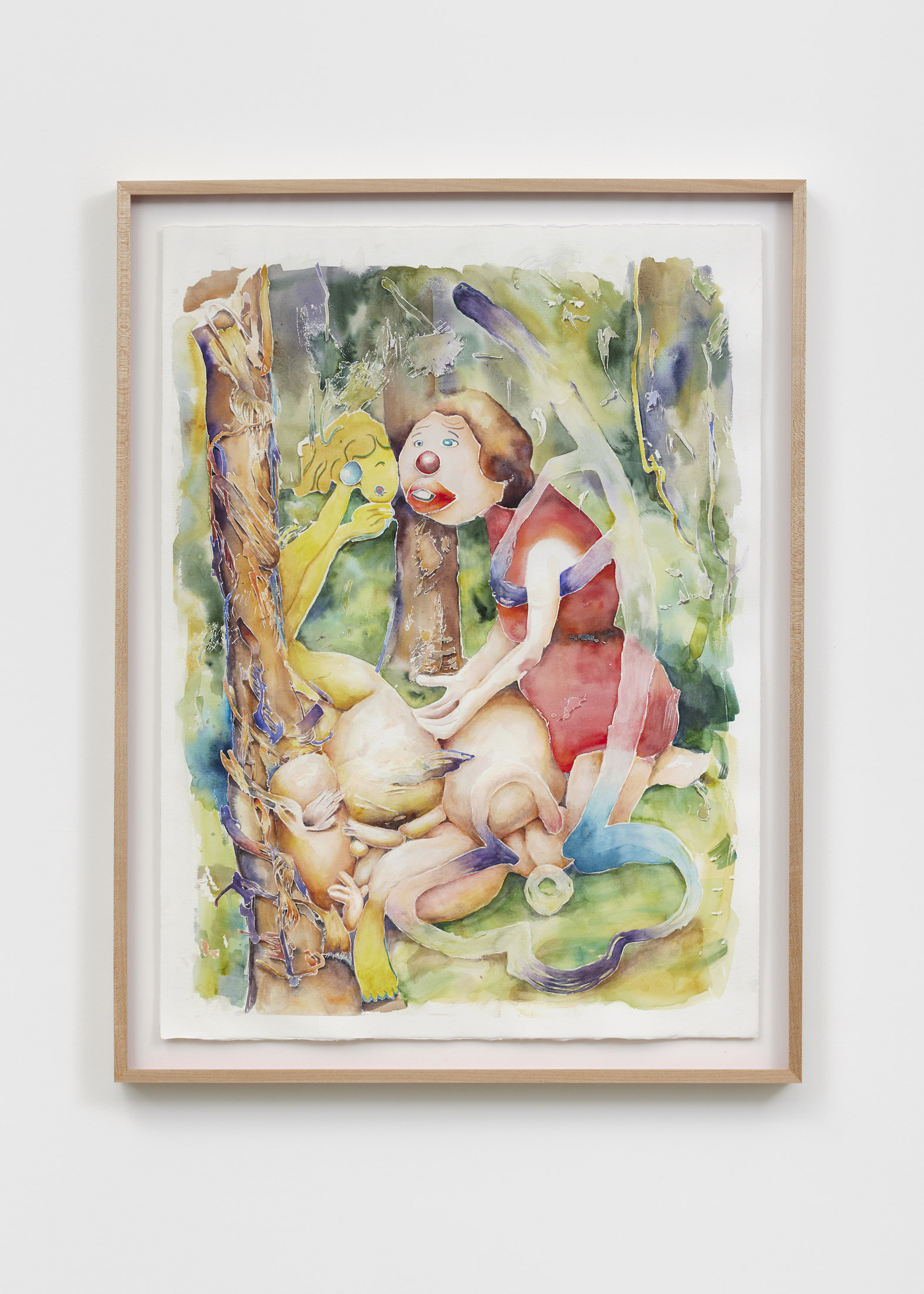

Beth Frey’s work, exemplified in Dither and Hum, lives in all the gaps: straddling physical and virtual worlds, her figures are at home in the great big open spaces (surveilled of course) of all the unanswered questions, and bask in the patient, observant, electrical eyes. Zoom in. Born out of complex and organic processes, and loaded with the very contradictions and intangibilities attached to representations of the body and gender, Frey’s figures and environments, are at once, familiar and fantastical. Using text, descriptions, rules, parameters, as a starting point, Frey engages with readily available digital technologies, treating them as both toy and tool, play and plunder. Inputting visual elements and vocal descriptions from sources that may include natural disasters, science fiction or tropes within classical painting, Beth Frey manipulates Artificial Intelligence to arrive at abstracted self-portraits that frolic in a bucolic but sinister universe. Bringing the completion of her works back to the analogue domain, Frey’s hand-rendered watercolours and animations embody physicality with unshakeable digital traces, strangely like the conflicted world we inhabit.

If there were no mirrors, would the world be easier?” iv – even hypothetically, that’s an unreasonably stupid question… “…then something awful would happen. The veil of reality would be ripped away.”v

[i] Woman’s Embodied Self: Feminist Perspectives on Identity and Image, by J. C. Chrisler and I. Johnston-Robledo. Copyright © 2018 the American Psychological Association.

[ii] At a loose end in Auckland airport, I googled “physics and mirrors”, and amused myself for at least fifteen minutes (flight delayed):

“Is my iPhone camera an accurate representation of what I look like? It makes my head look big, but the bathroom mirror makes my head look small!”

“Why do I look pretty in the mirror, but ugly and asymmetrical in flipped phone photos?”

“I think of myself as attractive… but when I take a photo I look BAD and different. Do I look like I do in the mirror? PLEASE.”

“If I look super hot in the mirror and super ugly in selfies, WHAT AM I? “How do I know what other people see me like in real life?”

Etc,. etc.,

[iii]London is often touted as one of the most surveilled cities in the world. Estimates for the number of CCTV cameras range between 627,700 and 942,500

[iv]Ibid ii

[v] Anne Enright, The Wren, The Wren.. Jonathan Cape 2023. Pg82